All My Favorite Poets are Mystics

My love for Mary Oliver, Rainer Maria Rilke, and David Whyte

I’m going to let you in on a dirty little secret. Even though I’ve been writing poetry for almost twenty years and have published several of my own collections, I don’t actually regularly read a lot of poetry from other people. Sure, I have a whole shelf of poetry books that includes authors ranging from Eliot and Auden to Frost and Collins and collections by friends who are fellow poets. And I do dip into these works from time to time. But don’t read poetry everyday. I also don’t subscribe to any regular literary journals with work by contemporary authors.

I could speculate as to any number of possible reasons why. Perhaps it’s because I’m a community college English professor who’s already engaging with a lot of literature and poetry and student writing (both creative and non-creative) on a daily basis. All I know is that I used to feel guilty about this but I really don’t anymore.

That said, I had an experience recently that crystallized for me which poets tend to resonate and stick with me.

I was out for a ride around Christmas and stopped at this old general store in our area that’s been converted into a cafe/pub/bookstore/gift shop. While perusing the shelves I noticed a copy of David Whyte’s collection The House of Belonging. Opening it, I flipped the pages randomly to “The Journey” and encountered these lines:

Sometimes everything

has to be

inscribed across

the heavens

so you can find

the one line

already written

inside you.

Suddenly I felt that familiar thrill of reading lines that set bells resonating through my whole being. I had similar feelings reading the title poem of that collection:

I awoke

this morning

in the gold light

turning this way

and that…

I immediately purchased the book, and have since purchased Whyte’s Pilgrim and Everything Is Waiting For You

As I was pondering what drew me to Whyte’s poetry, I realized that it’s what compels me to write my own poetry, which is that we are both mystics.

Poets write for different reasons: some write to offer incisive social commentary, others to probe their psychological innards before the public eye, others are wry, humorous observers, and some just like playing with words.

All of these are legitimate purposes for writing poetry. For myself, I’ve found that I write poetry as a way to get in touch with or express a sort of spiritual thrumming that I find humming in the world around me, particularly in nature.

So, the reason I can tell you that David Whyte is a mystic poet is simply—game recognize game. I resonate with his temperament because it is my own.

The more I pondered this though, the more I realized that my other favorite poets, the ones whose work has seeped into my bones, also have this mystic temperament, namely Mary Oliver and Rainer Maria Rilke.

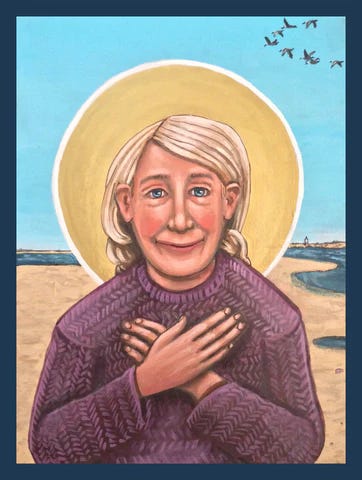

(Mary Oliver icon by Kelly Latimore)

Mary Oliver’s poetry has been criticized by some as simplistic and sort of self-helpy, and I’m sure that a search of Instagram would probably reveal a few repeated famous lines of hers set over and over against beautiful backgrounds. I probably would have joined in this criticism earlier in my poetic career, insecure and afraid of being lumped in with something so seemingly “unsophisticated”. But as I’ve gotten older and hopefully a little wiser (and honestly having less f—s to give about what people think) I’ve come to appreciate the spiritual simplicity of Oliver’s work. Consider her poem “When I Am Among The Trees”:

When I am among the trees,

especially the willows and the honey locust,

equally the beech, the oaks and the pines,

they give off such hints of gladness.

I would almost say that they save me, and daily.

I am so distant from the hope of myself,

in which I have goodness, and discernment,

and never hurry through the world

but walk slowly, and bow often.

Around me the trees stir in their leaves

and call out, “Stay awhile.”

The light flows from their branches.

And they call again, “It's simple,” they say,

“and you too have come

into the world to do this, to go easy, to be filled

with light, and to shine.”

Or her poem “Praying”

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

Sarah Todd writes, “The solace so many find in Oliver’s poems has everything to do with her ability to convey the joy of connectedness, of moving, even temporarily, beyond the limitations of self-consciousness into an experience of something unquestionably bigger.”

At this point in my life, rather than looking down on her poetry, I consider Mary Oliver’s way of seeing as a model to emulate.

I really came to appreciate the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke during a dark time in my life that I’ve written more about at length elsewhere.

Rilke was a young German poet who had a profound encounter with Orthodox Christianity and iconography during a trip to Russia in 1899. Shortly thereafter he began working on a cycle of poems he called “the prayers,” which would later make up the first part of The Book of Hours, the first of his mature poetic works. In these poems Rilke seems to write at times through the persona of a young monk or priest, and at other times through the perspective of the Divine. For example, this poem from the perspective of the monk has for me resonated with my experience of encountering and understanding God in recent years:

I live my life in widening circles

that reach out across the world.

I may not complete this last one

but I will give myself to it.

I circle around God, around the primordial tower.

I’ve been circling for thousands of years

and I still don’t know: am I a falcon,

a storm, or a great song?

But then this poem reads like God speaking to each newborn soul as it enters the world:

God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.

Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don’t let yourself lose me.

Nearby is the country they call life.

You will know it by its seriousness.

Give me your hand.

As opposed to Mary Oliver, who finds the Divine in the forests and fields, Rilke seems to find himself feeling his way through dim, candle-lit monastic corridors as God flits just ahead.

I can understand why some would find this extremely frustrating. They want clarity and certainty, and I get that. I’ve been there at one point in my life.

I only speak for myself when I say that, at this point in my life, given my own experience, I think clarity and certainty are to a large extent illusory. Now I’m not saying Truth or Reality or God aren’t out there or real. I just tend to experience them in moments and in feelings, in the way a tree blows or the sun sets, in a hug from a friend or a song at church. In that moment I know in my bones that something is deeply Real, and then the veil sweeps over again. But I’ve also found, and I see this in the poets I’ve discussed here, that we can have these encounters more often by pressing up against the veil in hopes it will part once more. This takes patience, but it is worth it.

As Rilke writes elsewhere in his Letters to a Young Poet, “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

I've always loved that Rilke line: "Flare up like a flame / and make big shadows I can move in."

I resonate with so much of this. Big fan of the mystics as well!

A fellow mystic here. Thanks for sharing!!