Living on the Edge of the Inside

Finding our place as artists

Lately I’ve been reading Richard Rohr’s book Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi. Rohr is himself a Franciscan, and in the book is attempting to expound Franciscan spirituality for 21st century readers.

At one point in the book, Rohr writes something that I’ve been thinking about for days since:

Francis and Clare were not so much prophets by what they said as in the radical, system-critiquing way that they lived their lives. They found both their inner and outer freedom by structurally living on the edge of the inside of both church and society….By ‘living on the edge of the inside’ I mean building on the solid Tradition (‘from the inside’) but doing it from a new and creative stance where you cannot be coopted for purposes of security, possessions, or the illusion of power (‘on the edge’).

For one reason or another, I’ve been thinking about this concept of “the edge of the inside” in relation to being a certain kind of artist.

It’s had me thinking of a talk I heard Andy Crouch give at a conference a few years ago, where he was presenting the argument that artists need institutions, and institutions need artists. If I remember his basic contention correctly, his argument was that part of the task of artists is to provide critique and new perspective, while the goal of institutions was to preserve important ideas and traditions. He argued that artists need institutions to help stabilize and ground them as individuals, but institutions need the prophetic critique of artists to prevent them from stagnating and corrupting, as tends to happen over time.

I think this dovetails nicely with Rohr’s concept, because Crouch’s model begs the question of, if the artist is going to be part of the institution, where should they locate themselves in that institution? Rohr would say, on the edge of the inside.

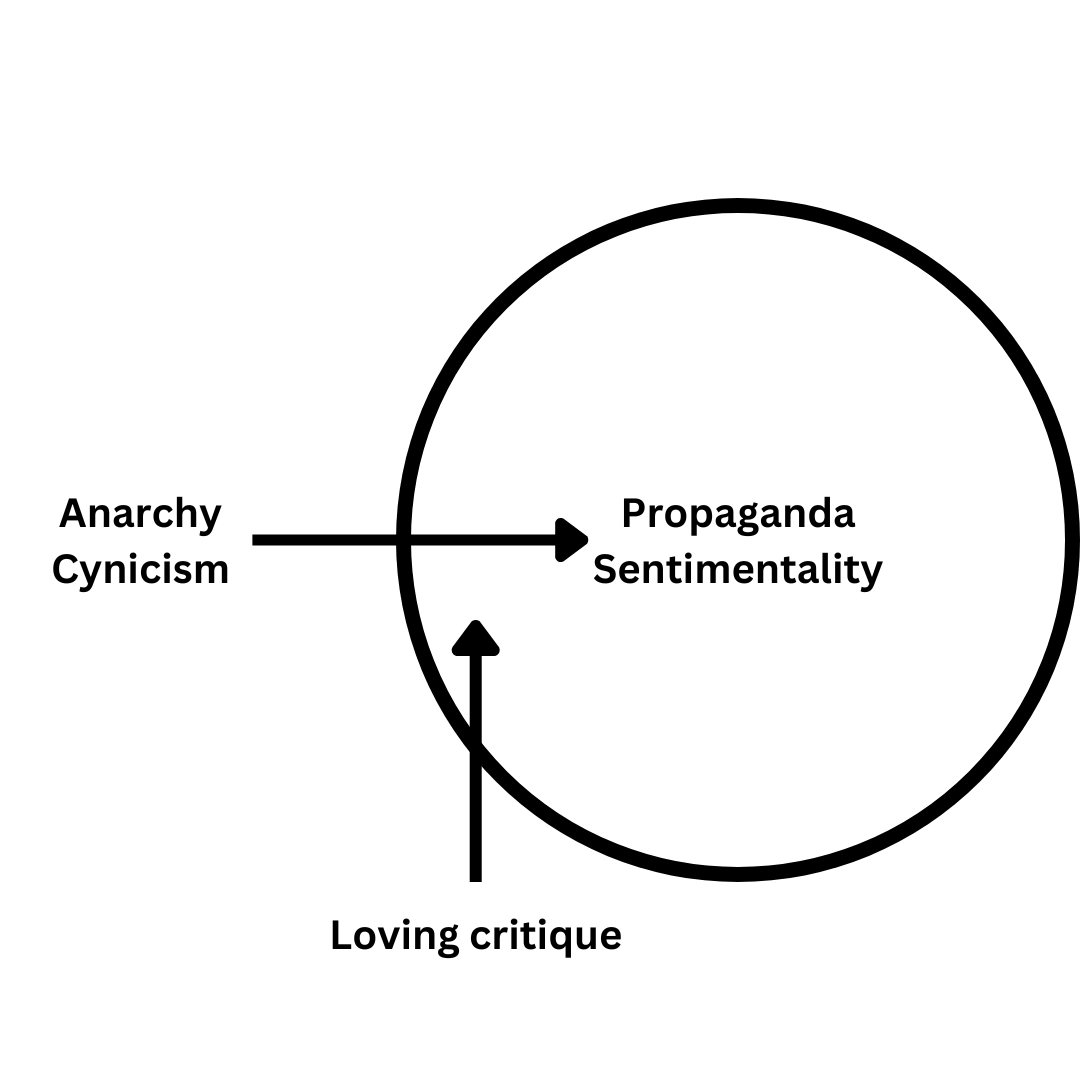

But why there? This is where I had to tease this out a little more with my wife, who offered up a brilliant insight. We can imagine the relationship of an artist and an institution like the graphic below. On one end of the spectrum, an artist finds themselves in an institution’s centers of power. The challenge with being here is that an artist’s work can quickly be co-opted for institutional propaganda, or it can be reduced to anemic sentimentality. The artist’s work has no real power of its own, it’s just blandly entertaining, or used in the service of pre-existing power.

On the other end of the spectrum however, an artist can reside so far outside an institution that they can be reduced to cynicism and anarchy, a kind of “burn it all down” mentality. The whole thing is corrupt and not worth saving.

However, if the artist exists on the edge of the inside of an institution, they are usually far enough away from the centers of institutional power to see and offer critique, but because they are still part of the institution and want to see it do well, the critique comes from a place of love.

I write all of this because I think we are in a time where we need the prophetic critique of artists now more than ever. Most of our societal institutions have been exposed as corrupt in some form or another, but it also seems like a lot of our art is either the anarchy of “F—k the system” or the shallow distraction of “Espresso”. These forms of art have their time and place, but they don’t really do much to actually call out the institutions that we need to reform in order to have a flourishing society.

We also live in a time where it is nigh impossible to live outside the system. We are all caught in the tangled, global webs of corporate capitalism. No one truly lives “off-grid” in our modern world.

So if we’re all stuck in what Dorothy Day called “the dirty, rotten system” but we don’t want to succumb to it, it seems that, going back to Rohr, we have to find our way to the edge. And I don’t think that edge is a universal line for everyone. I think we all have to find what that edge is for us. Or if nothing else we have to orient ourselves toward the edge, and away from the center.

A Lover’s War

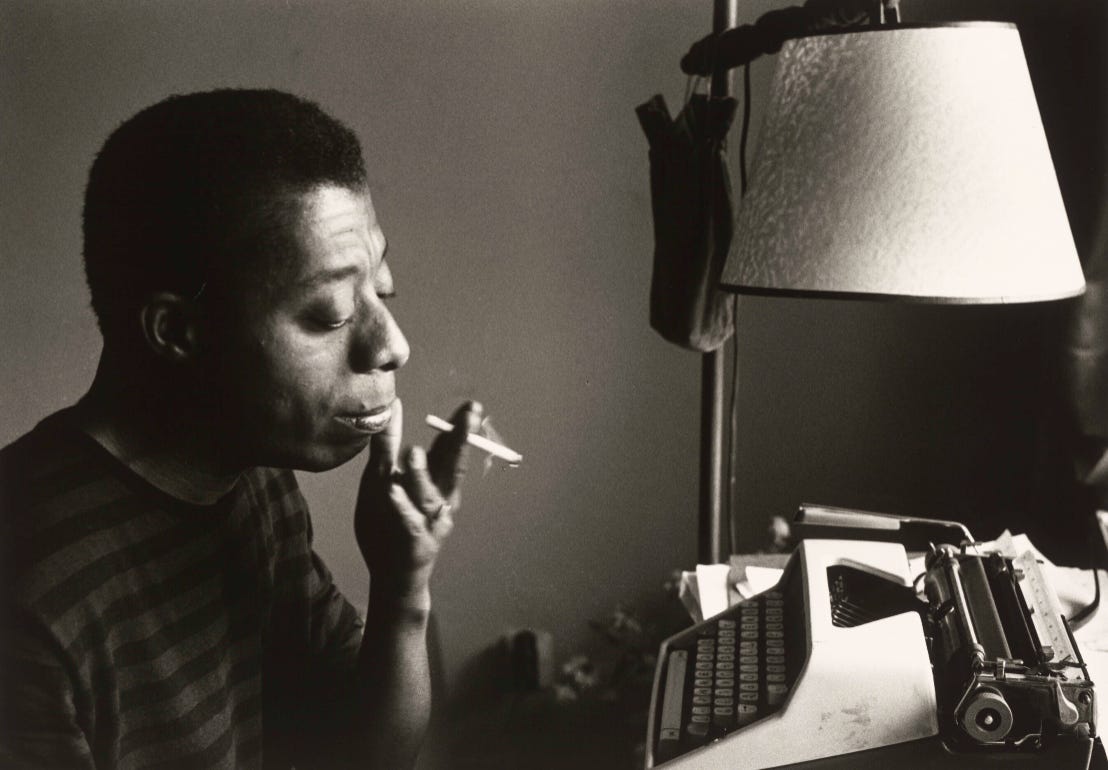

One artist who both lived this out and thought about it deeply was African-American writer James Baldwin. By virtue of being a queer black man in the heyday of Jim Crow and suburban white America, Baldwin was already a man on the edge of the inside. Baldwin embodies this position of loving critique in his famous quote, “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

In his essay “The Creative Process”, Baldwin says, “I am really trying to make clear the nature of the artist’s responsibility to his society. The peculiar nature of this responsibility is that he must never cease warring with it, for its sake and for his own.” He defines this warring in an interesting way, however: “[T]he war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.”

Baldwin points out in his essay that societies (we might add institutions) are formed “to create a bulwark against the inner and the outer chaos, in order to make life bearable and to keep the human race alive.” In that process traditions are created and perpetuated to the point that “the people, in general, will suppose [the tradition] to have existed from before the beginning of time and will be most unwilling and indeed unable to conceive of any changes in it.” This echoes Crouch’s points from above, which is that institutions are designed as stabilizing forces in society, but over time, their ways of being can become unquestioned and stagnate to the point of corruption. For Baldwin, the artist must help shake up this stagnation: “A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven….The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

Baldwin also notes that this vocation comes with a cost. The artist is often viewed as the “incorrigible disturber of the peace” who is “historically despised while living and acclaimed when safely dead”.

Illuminate the Dark

What I have outlined in this piece is a sober calling, which not every artist is called to fully embrace (although I think every artist inhabits this role in some small way at times). There is a counting of the cost that must be taken before engaging in such a venture. There may be times where we engage more deeply in this aspect of the artist than others. If there is any reward to be found in such work, it is, in the words of Baldwin, that we may help to “ illuminate [the] darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.”